He was the last to be carried out of the evac (or as the locals say to avoid bad omens, “the latest”). He has tension pneumothorax. A pleural drain is sticking out of his lungs. He’s trying to crack jokes and really wants to smoke. We don’t let him at first, but eventually we give in. This is the first time in my life that I have seen a person with a drainage tube coming out of their lungs through the back while he’s puffing on a cigarette with such earnest delight. He is one of the injured soldiers we’re evacuating.

This is a story about medical evacuation with one of the teams of Hospitaliers, who works on the evacuation bus “Avstriyka”. As November 18, 2023, the “Avstriyka” was transporting 2,405 wounded soldiers.

Text by Daryna Anastasieva

Translated by Daniil Korsunskyi

Photo by Ilmar Raag

Base 19:15. A call.

We left the base at 19:30. A call comes in, 10 minutes to get ready, and the team is already sitting in Avstriyka: the hospitallers have received a request for medevac. Avstriyka is the codename of a bus with medical equipment named in honor of a volunteer fallen last summer, outfitted for transporting people with injuries of various severities. This time, the team consists of eight hospitallers: Katia, Lastivka, Varta, Astra, Dripper, Kevin, Advokat, and Helga. Most of them are between 18 to 28 years old. Calm, focused, optimistic. They have all finished their education, medical and physical training, and this is their first ride. Katia, the team leader and anesthesiologist by trade, is preparing the team to receive the wounded.

“Look: the most important thing is to talk. There’s people that don’t want to talk, that want to be left alone. You can tell immediately when interfering will only make things worse. But more often than not, when a person is left alone with their thoughts and their anxieties, and especially if it’s an amputee, then driving for three hours and thinking about the leg they’ve lost is very psychologically taxing. This is why I’m asking you to try to gently find your way around everyone: talk to them, find something they would be interested in: everyone has their pick. Some like to talk about their families. It inspires them, revitalizes them, and they can go on and on about their wives and kids. For others, that can be a bad subject. For example, they might’ve gone through a divorce just before the war. Sometimes they can ask to charge their phone for a call, if there’s a charger under every bed where you can plug your phone in, and if needed, call their families. There will be some patients that can eat and drink, you can offer them cookies, water, or juice, but there will be others that can’t have anything at all.”

After receiving such guidance, the cab goes quiet and everyone retreats into their own thoughts. The bus is entering Donetsk Oblast.

Hospital No.1. 21:15.

Two hours after we had arrived on site, the evac stops next to the hospital. The grim ambience of a frontline city, the tense silence, shadowed faces of soldiers and doctors alike, waiting in nervous silence for the first batch of the wounded. We don’t know how bad their injuries will be yet. Only in a few hours, will I learn that this was a light ride, in that on this mission, all patients managed to avoid amputation and made it to the hospital without any complications. The hospitallers also go out to ground zero to drag the fighters out of the trenches and drive them to field hospitals every day, and those calls are a whole different story.

Katia disappears in the reception room. She needs to know the kinds of injuries the soldiers have today. A buzzing light bulb and the weak lights from inside our Avstriyka are all the light there is for kilometres. I lift my head for a moment and see the star-filled sky, the sky of my dear Donetsk that only exists here. I imagine that I am 10 years old again, that my parents and I have gone camping at the Blue Lakes and I am looking at the stars before bedtime. For ten years now, I see that peaceful sky only in my memories: that scenery has been etched into my mind forever. I’m pulled back into reality by the creak of a trolley. They’re wheeling out the first one already. Katia approaches him with a friendly smile, already flipping through his medical records.

“Hi, what’s your name?”

“Slavik.”

“What are your injuries, Slavik, where does it hurt?”

“Stomach. And also around the shoulder blade.”

“Anything else besides the stomach and shoulder blade?”

“No.”

“I’ll check form 100 very quickly and if we can give you anything, we’ll do it inside.”

She lifts the blanket, compares the data, and waves down the team to take him away. Another one gets wheeled out right after him. The boys are preparing the stretchers:

“Everyone ready? On one-two — lift!”

They’re holding up the wounded man from all sides as they carry him into the bus. A lot of strength is needed to gently lift a patient two meters up into the evac through a narrow opening while keeping him perfectly horizontal (some fighters can weigh more than 120 kg). A piss bottle falls out from under the covers and onto the asphalt. They argue, whether to put it back or keep lifting. Finally, the patient is inside. “Don’t put that one on oxygen,” Katia orders. They get the soldier hooked up to all necessary systems, cover him with a thermal blanket, change their nitrile gloves out for new ones and go to get the next one. Emotional contact with the patient is right up there beside physical care in terms of importance, so there’s a hospitaller staying behind with every hospitalised soldier.

The air raid alarm rings out. Nobody pays it any mind, though it irritates me: here at home, in the East, there are missiles flying in just about every day, and the Telegram channels and news outlets only mention the ones where people die or get injured. Danger feels different than in Kyiv, Lviv, or Odesa. You can physically feel it in the air, and not just because of the missiles, but also because of the much more frequent shellings with rocket artillery, aerial bombs, and UAVs.

With quick and coordinated motions, and formulaic precision, the second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth injured patients are brought into Avstriyka’s cab. Some have their heads wrapped in bandages, some their limbs, others are covered from head to toe altogether. With each one, there’s a short dialogue, “one-two — lift,” and here they are, all on board. We can’t take any more on board today. There’s people gathering on the street outside the bus, soldiers that can still move on their own. The evac can fit nine more “sitting” patients, four in the front and four in the back. Some are in wheelchairs, others have crutches, some are holding urine bottles in hand, others have blood bags. Their afflictions include multiple gunshot wounds fractures, Tension pneumothorax, shrapnel wounds, mortar blast injuries, concussion/post-concussion syndrome.

![]()

One of them, a man with his face covered in laryngeal tubes, asks for water. Katia warns that it’ll go up his nose: because of his diagnosis, the wounded man has to take any liquids through those tubes. Eventually she lets him take one tiny sip, just to freshen up his mouth.

None of the soldiers break the silence, though the pain is already sewn into their future scars, their stiff motions and glassy stares.

Work is bustling inside the bus, both medical and psychological support is being provided left and right. Each bed is equipped with a monitor that allows the team to track everyone’s vital signs: pulse, blood pressure, O2 saturation, ECG. Oxygen, infusion machines, aspirators, a defibrillator, and artificial ventilation machine are all on standby for quick access as needed. There’s a special box for warming up solutions, and a similar one for infusions is right next to it.

The personnel will be standing the whole trip. I get on board last, scared of getting in the way, scared of being in an enclosed space with so much pain. Eventually I make up my mind, swallow another breath that smells like home, and the doors close behind me. We leave. Avstriyka starts to move along a dark road, and in it there are dozens of hands making the work light. I’m seated in the front part of the bus, beside the “sitting” patients. We’re driving in silence. Suddenly we come to a stop, a doctor runs into the cab and addresses one of the soldiers: “Andrii and Ivan got out, they’re both in critical care. Surgery is done, they’ve managed to save their legs, they’re stable. Rest easy and heal up, your comrades are safe.” A barely noticeable smile pulls at the corners of his mouth, a silent thanks in his eyes: now we can keep going.

Existential thoughts come easy when you’re in a bus full of wounded soldiers. It’s nighttime. Cars with AH on their license plates under the Donetsk sky. Avstriyka drives ever onward through the silence of industrial towns and their demolished roads.

The driver is careful not to go off-road, where the incoming traffic goes when they see us. The inside of the us is total silence, broken only by the occasional gentle voice of a hospitaller. The soldiers are quiet. Some are writing back to their families, others are checking the news, the ones in the worst condition are delirious. The smells are mixed: blood, urine, sweat, antiseptics, and energy drinks. The teamwork is well-coordinated even though this is the team’s first call. A paramedic is on standby next to every patient, as they need to keep contact. Some are having their blankets changed, others need fluid drainage, some are helping hold up oxygen masks. It’s important to always keep an eye out, because any “sitting” patient can quickly become a “lying” one, and any “lying” patient can always get worse.

The bus drives through the eastern steppe, passing through security checkpoints. The driver keeps some distance with the vehicle accompanying us, because that way it’s easier to see the road and we’ll be warned if there are cars without lights parked beside the road. The driver also asks the accompanying car to warn him of any “trampolines”: holes and bumps in the road, as the patients are too delicate for that. Little by little, the soldiers start talking among themselves: some have just met each other. They talk about their injuries and how they got them. The drive will last for another hour. One of the bed-ridden fighters agrees to talk to me. He’s 59 years old, and this is his second injury. He has trauma on both of his legs and incredibly bright eyes.

“I’m an infantryman,” he says, “serving since the first day of the full-scale invasion. I worked as an electrician in Bila Tserkva before that. When we were out on a mission, a shell landed in our vehicle. I didn’t even understand what happened at first. By the time the fourth shell landed, it felt like a tank was firing on us. We fell to the ground, went prone, and waited for all the munitions to go off, because help might not come while they’re still exploding, and we can’t risk losing people. You know, they prioritise healthy people over the wounded ones in the war.”

When asked what he will do after recovering, he says he’ll go back to the army. Helga is standing next to me, a quiet girl with very steady hands. She’s checking if the patient is handling our conversation fine, if his state hasn’t worsened from the nerves.

There’s beeping coming from the neighboring bed: one of the patients had his blood pressure shoot up. Katia is next to him in the blink of an eye. Everyone breathes a sigh of relief, as with her skilled hands, he’s stable again. Now the only thing we hear is the synchronised beeping of tonometers and thermometers, occasionally joined by notifications from messenger apps. Avstriyka slowly drifts to sleep as the soldiers pass out from the injuries, memories, and painkillers. Hospitallers sit down on the floor, this is their fifth hour on foot. There is finally comfort, as comfortable as it can be in such a situation. Relocation of the wounded is still ahead of us.

Hospital no.2. 00:15.

The second hospital is much more well-lit and lively. The cool autumn air nips at the skin and gives everyone a boost for the next step. Senior medics from the hospital greet us with an unwelcoming “this is the second bus today,” but get to work right away. They bring out the trolleys and put down blankets. Loading off the wounded is even harder than bringing them into the bus or transporting them. The boys are brought out nearly naked and immediately covered up. They go through check-ups, their respective conditions are confirmed. Every other one asks for a smoke. The doctors shrug, but allow it. One soldier with head and hand trauma can’t hold the cigarette on his own, so Lastivka steps in to help him. “All inclusive,” she says, letting him take a drag and ashing the cigarette.

They carry out the guy with tension pneumothorax last. He starts “acting up,” falling into hysterics, trying to struggle, which only worsens his state. He says it hurts, to which the carriers stoically reply: “If you fall out right now, it will be even worse.” The contorted soldier ends up in a hospital trolley, hospitallers are calming him down, and he demands a cigarette. Once he gets it, he calms down again.

Those that can walk on their own power obediently go from the bus to the hospital. Even then, Avstriyka still stinks of wounds, fumbled bedsheets, open medication, and still-warm blankets. The team says goodbye to each and every soldier: they make arrangements to meet for coffee in Kyiv, crack jokes, wipe tears, give hugs. In these past few hours in the evac, a community was born, forever connected by compassion, warmth, and a shared fight. At some point one of the medics turns to me and asks: “Are you going to stand there, or will you help get this guy inside?” I clumsily grab the stretchers and help wheel the injured man into the hospital.

When the latest trolley is brought into the hospital corridor, we head off to base. Work is in full swing even on the way back, we need to sanitize the cab, clear out the trash, repackage and organise the medicine. The last half hour we drive without a word, another shade of silence to that which already permeates the air. Hospitallers lie down in beds that just an hour ago were holding the injured. Some have a nap, some read the news. An air of productive exhaustion hangs above the team.

3:00. Base. Return.

Everyone quickly has dinner, has a shower, and goes to rest, while Katia and I remain in the kitchen, where we will stay until five in the morning. Despite being completely exhausted, something is holding us together. We talk about how the East “pulls you in,” how we can’t live without it for long. Katia tells me about the sunflowers, which were bright yellow just two weeks ago but have now bowed their heads down, and yet, even tired, they stay beautiful. She tells me about her day job in one of the hospitals in Kyiv, where she took a vacation to be with the Hospitallers. All of them are volunteers, saving lives without any reward. And while she loves and values her job, where she saves lives as well, she still can’t live without these trips: “To be a sunflower in the steppes of Donbas is to know how to live and what to die for.” I respond with my favorite “black caravan” [Both of these are quotes from poems by Serhiy Zhadan.]

Katia’s path as a hospitaller began with a different evacuation bus, Kraken, which last year ended up in a horrible accident where her colleague by the callsign “Avstriyka” died. Now Katia drives around in a new bus, named in her honor and painted by Irena Mykoliv.

At some point Katia stands up and shows me a scar on her leg: a long stitch going down her thigh, where she has lost all feeling. She shows me pictures of her recovery, which lasted 8 months, tells me how she learned to drift in her wheelchair, how she would get visits from a surgeon-in-arms who was in the same accident and received a traumatic amputation, and has since come back to hospitallers and is now again going out on missions. Her eyes shine like the stars above the hospital. It’s already four in the morning, we’re making our third cup of tea, the rest of the team is asleep. We talk about how we happened to live in a time where war steals away people’s fates (if only their fates), where the skies are abuzz with military aircraft but we’re calm: we know they’re ours. It’s always calm in the company of medics and soldiers. Everything is clearly defined: there’s good and there’s bad, there’s white and black. “There’s also red,” says Katia, “that’s blood.” “It’s also love,” I add. In the end, we decide to bed down for the night. It’s early rising tomorrow, lots of things to do. And besides, a new call could come in any second now.

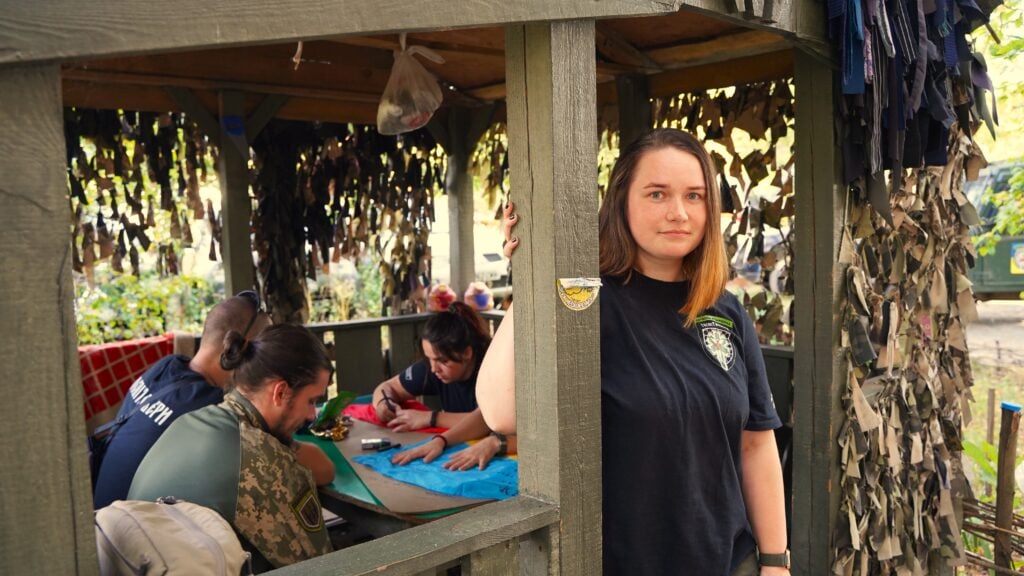

The next morning

The sun wakes me, I brew a cup of coffee and go outside, where yesterday’s heroes are already hard at work. The eldest of the team, Varta, is sitting on a bench. This was her latest mission before vacation, today she’s going home. She tells her story:

“I signed up with the Hospitallers in ‘19, when a close friend of mine was killed, a marine from the 36th brigade. I thought I’d feel better once I pass the teachings. I was just getting by. I didn’t feel better. Decided to drive out for at least one rotation, and I’m still here. Got pulled in. It was scary at first, when we ended up in Marinka. Constant shootings, explosions. I went to sleep thinking I wouldn’t wake up tomorrow. But then I woke up, and the fear went away.”

In a nearby gazebo I see Dripper and Advokat, the ones who carried the stretchers yesterday. They’re old friends, strong and tall guys a bit over 20 years old. I ask them how the first call went, they say that they expected worse and want to go to the “meat grinder,” closer to the front lines and harder locations. I look at their young faces, which in peaceful times would be building relationships and careers. And this age of theirs, the best age to live, gets spent on war. Few here think what they will do afterward. They just do their job, just save lives, just protect our country, just make miracles every day. I ask Dripper and Advokat what they would do to a wounded Russian, to which they instantly respond: “Geneva convention. We all signed it, and we’ll give medical aid to all wounded in accordance with the triage system.”

We are joined by Lastivka, who begins singing: “I will go to distant mountains…,” [Lyrics from a song by the same name by Volodymyr Ivasiuk] the rest of the team comes together around us. They’re drinking tea, reading books, doing everyday chores. From the outside in, it almost looks like some kind of downshifting camp. But in this camp there is no day or night, no weekdays and weekends, only the time between calls, where they pass their lives and save thousands of others.